Clonmacnoise: a pictorial tour

Niall C.E.J. O'Brien

The monastic and episcopal site of Clonmacnoise holds a special place in the hearts and minds of Irish people and those who follow the ecclesiastical history of the country. I first visited Clonmacnoise in the mid 1990s arriving near dawn in the month of May. The sun was just brightening the eastern sky. The first image to strike my senses was not the architectural riches of Clonmacnoise but birds singing across the broad expanse of the River Shannon and the flat country beyond to the north and west. For a person who comes from a part of Ireland of hills and valleys the flatness of the countryside was like a different world. But it was the birds that day that felt my heart and they have always reminded me of Clonmacnoise wherever I hear the small birds sing.

When I returned in 2016, towards evening time of a September day, the birds were just heading off home while the beauty of the broad River Shannon flowed by. On that day I approached the monastic site from the east, along a straight road but one full of inclines and declines so that Clonmacnoise almost comes upon you without warning. I didn't have a camera on my first visit but made up for it on the second. This article is as much as pictorial tour, as the title says, of Clonmacnoise rather than the detailed history articles that I am use to but then Clonmacnoise is a different world!

Introduction

The monastery at

Clonmacnoise was founded in the sixth century by St. Ciaran. St. Ciaran was

educated by St. Finnian of Clonard and St. Enda of Aran and was listed among

the ‘twelve apostles of Ireland’. Within a short time Clonmacnoise became one

of the important religious centres in pre-Viking Ireland. This was due to the personalities

of its abbots and its famous school where many famous manuscripts were made

such as the Annals of Tighernach (11th century) and the Book of the

Dun Cow (12th century). Clonmacnoise was also well served by its

location at the centre of Ireland with the River Shannon giving easy

communication north and south and the Esker Riada for east-west travel. The river

location also brought trouble as Clonmacnoise was plundered at least six times

between 834 and 1012. Of more economic harm the monastery suffered destruction

by fire 26 times between 841 and 1204. [Peter Harbison, Guide to National and Historic Monuments of Ireland (Gill &

Macmillan, Dublin, 1992), p. 276]

Possibly because of the

conservative views of the abbots of Clonmacnoise and other political

influences, Clonmacnoise was not recognised as the cathedral church of a

diocese at the synod of Rathbreasail (1111). Later it was recognised as the

centre for the new diocese of West Meath with Clonard as the centre for the

diocese of East Meath. Yet no bishop is known by name until 1148 and

Muidchertach O Maeluidhir. Sometime after 1174 the diocese of Clonmacnoise was

transferred from the province of Tuam to that of Armagh. After the Norman

invasion the new Bishop of Meath pushed the Bishop of Clonard westwards at the

expense of Clonmacnoise. By the mid-thirteenth century the diocese was reduced

to a small area east of the River Shannon. Thus Clonmacnoise, rich in architectural

and natural beauty became one of the poorest dioceses. [A. Gwynn & R.N.

Hadcock, Medieval Religious Houses

Ireland (Irish Academic Press, Blackrock, 1988), p. 64]

To add to its decline

and economic troubles Clonmacnoise was often plundered in medieval times

beginning in 1179 when the Normans attacked. In 1552 the English garrison from

Athlone attacked the site and removed all the monastic valuables they could

find. From that time Clonmacnoise never recovered. [Peter Harbison, Guide to National and Historic Monuments of

Ireland (Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1992), p. 276]

The wide River Shannon as it passes by Clonmacnoise

Clonmacnoise as seen from the river bank

Northern view of the churches of Clonmacnoise

==========

Teampull Finghin

On the northern boundary wall of the Clonmacnoise site is the twelfth century nave and chancel of Teampull Finghin. the Romanesque chancel arch is a fine example. It appears that the nave and chancel were built at the same time. At a different time a round tower was built onto the south side of the church. [Brian de Breffny & George Mott, The Churches and Abbeys of Ireland (Thames & Hudson, London, 1976), p. 41]

Teampull Finghin with its attached round tower

Teampull Finghin chancel arch and nave in foreground

Teampull Finghin chancel arch

West archway/window with Temple Connor and the round tower beyond

==============

Clonmacnoise cathedral

Clonmacnoise was recognised as the centre of a diocese in the early twelfth century and so needed a cathedral church to display its new status. The building that was adopted as the cathedral already a standing church long before that time and was even described as restored in 910 which would make its actually construction much earlier. The cathedral appears to be the building referred to as the daimliag or stone church.

The west doorway as seen

today is a fine example of a Romanesque doorway but it is a reconstruction. Plate

four of Roger Stalley’s study on Irish high crosses shows the arch under reconstruction

with another broad arch clearly visible above the doorway and extending beyond

the doorway [Roger Stalley, Irish High

Crosses (Country House, Dublin, 1996), p. 20]. The smaller and newer

Romanesque west doorway is dated to the fifteenth century when about the same

time the chancel area was divided into three vaulted chapels.

In about 910 the cathedral

itself was restored by Abbot Colman Mac Aillel and Flann Sinna, the High King. Further

work was done between 1080 and 1104 by Cormac son of Connor and Flaherty O’Lynch.

The sculptured north doorway was built about 1460 by dean Odo with the figures

of St. Francis, St. Patrick and St. Dominic overhead. [Peter Harbison, Guide to National and Historic Monuments of

Ireland (Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1992), p. 277]

Cathedral church from NW with Temple Doolin in the background

West doorway of the cathedral

Detail of the inside of the cathedral west doorway

North doorway of cathedral with south doorway beyond

Inside the north wall of the cathedral

Inside the south wall of the cathedral

Inside south wall of the cathedral with door to right into the sacristy

Inside the cathedral from outside the east wall

Looking into the cathedral from outside the south window

note the different ground levels

==============

The cathedral and the position of he high crosses was carefully arranged so as to form the sign of the cross over the central feature of the monastic enclosure. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale University Press, 2010), p. 68]

==============

Clonmacnoise high crosses

Clonmacnoise has two

high crosses and a fragmentary high cross along with some tomb slabs of early

date. One of these tomb slabs is dedicated to ‘Thuathal saer’ or Thuathal the

craftsman. The style of figures on the Cross of the Scriptures is sufficiently

close to that of crosses at Durrow and Monasterboice to say they craftsmen

travelled extensively across the Midlands – perhaps Thuathal was one of these

people. Although experts can say for certain that they know the meaning of the

various depictions on the Cross of the Scriptures many images are still a

mystery such as some of the side panels. The hunting scenes and horsemen are

known on other crosses and even have similarity with Pictish sculptors in

Scotland – Iona was more than just a place. Of the known depictions on the west

side of the Cross of the Scriptures include – the crucifixion of Christ along

with his arrest – the resurrection along with Christ receiving the breath of

life from a bird representing the Holy Spirit. On the east side the images

include the Last Judgement and what is thought to be King Diarmuit and St. Ciaran

on the founding of Clonmacnoise. Over the centuries high crosses such as those

at Clonmacnoise have weathered considerably and a number have being brought

indoors such as at Clonmacnoise. [Roger Stalley, Irish High Crosses (Country House, Dublin, 1996), pp. 5, 7, 13, 36,

37]

The east side of the Cross of the Scriptures

West side of the Cross of the Scriptures with cathedral in background

South high cross with the two churches of

Teample Doolin (left) & Temple Hurpan (right) in background

==============

West end of Temple Hurpan (left) - cathedral centre and edge of Temple Ri (right)

==============

Temple

Doolin and Temple Hurpan

To the south of the

cathedral stand two attached churches. The western church, called Temple Doolin

has an antae and a round headed east window. It was restored in 1689 by Edward

Dowling who inserted a new doorway. The church called Temple Hurpan was added

on to the east end of Temple Doolin in the seventeenth century. [Peter

Harbison, Guide to National and Historic

Monuments of Ireland (Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1992), p. 277]

Temple Doolin is possibly of eleventh century construction. It appears to have functioned as the parish church but this designation may be of later date. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale University Press, 2010), p. 225]

Temple Doolin is possibly of eleventh century construction. It appears to have functioned as the parish church but this designation may be of later date. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale University Press, 2010), p. 225]

Inside Temple Doolin facing east

Temple Hurpan as seen through the east window of Temple Doolin

Temple Doolin seen through the east window from inside Temple Hurpan

Doorway into Temple Hurpan with main round tower in the background

==============

Temple

Ri or Teampull Melaghlin

This church was built

about 1200 and has some fine lancet east windows and a gallery at the western

end. The sixteenth century south doorway was a later insertion. [Peter

Harbison, Guide to National and Historic

Monuments of Ireland (Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1992), p. 277]

The church was

patronised by the Uí Mael Sechnaill royal family of Meath and was possibly used

as a private chapel for the family when visiting Clonmacnoise. It could also

have served as a mortuary chapel for the family. When the church was built it was given a south doorway instead of the old west door arrangement. It is one of the few churches to have a south doorway along with gable corbels. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale

University Press, 2010), pp. 223, 225]

South side of Temple Ri

Old and new south doorway of Temple Ri

East windows of Temple Ri

Looking out the doorway of Temple Ri

==============

Temple

Kieran

This is one of the

smallest buildings in the Clonmacnoise monastic enclosure. The oratory with

antae is much mutilated. It is said that St. Ciaran was buried in the

north-western corner of the building. [Peter Harbison, Guide to National and Historic Monuments of Ireland (Gill &

Macmillan, Dublin, 1992), p. 277] This building reminds one of Ardmore in Co.

Waterford where the founding saint, St. Declan, is buried in a detached oratory

some distance away from the cathedral. In later times the Continental religious

orders buried their founding patrons within the chief church and near the high

altar as was the case in many a parish church.

The alignment of Temple Kieran is north-east to south-west. This is different from the cathedral and the other churches around it which are on an east-west axis. Some scholars say the idea of the east-west axis was conceived as early as 700 but Temple Kieran follows the line of early graves which are north-east to south-west. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale University Press, 2010), p. 68]

The alignment of Temple Kieran is north-east to south-west. This is different from the cathedral and the other churches around it which are on an east-west axis. Some scholars say the idea of the east-west axis was conceived as early as 700 but Temple Kieran follows the line of early graves which are north-east to south-west. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale University Press, 2010), p. 68]

Temple Kieran

Clonmacnoise round towers

Clonmacnoise has two round towers - one free standing and the other attached to Teampull Finghin. The round tower attached to Teampull Finghin once had a cap built with specially cut stones arranged in a herringbone pattern. The attached round tower is a rare example of this arrangement in Ireland. Most round towers were detached, free standing structures. The Teampull Finghin example displays the purpose of the round tower as a belfry to call the religious to pray. [Roger Stalley, Irish Round Towers (Country House, Dublin, 2000), p. 33]

The main free standing

round tower at Clonmacnoise is to the north-west of the cathedral entrance

which location was the standard arrangement at most sites that have a round

tower. The annals tell us that it was finished in 1124 under the direction of

Abbot Gillachrist Ua Maoileoin and King Turlough O’Connor. The tower is built

of two halves. The bottom half is built using well-dressed ashlar stone, characteristic

of the twelfth century while the top half was done using coarser worked stone

that you see more in buildings constructed before 1100. [Roger Stalley, Irish Round Towers (Country House,

Dublin, 2000), pp. 7, 14, 15]

Conleth Manning has suggested that the stones which fell from the top of the round tower were used to build the small tower by Teampull Finghin. [Conleth Manning, 'Some early masonry churches and the round tower', in Clonmacnoise Studies Volume 2 seminar papers 1998 (Stationery Office, Dublin, 2003), p. 91]

Conleth Manning has suggested that the stones which fell from the top of the round tower were used to build the small tower by Teampull Finghin. [Conleth Manning, 'Some early masonry churches and the round tower', in Clonmacnoise Studies Volume 2 seminar papers 1998 (Stationery Office, Dublin, 2003), p. 91]

Main round tower as seen from the River Shannon approach

The round tower from the north-east

Round tower on south side of Teampull Finghin

===============

Teampull Connor

Teampull Connor with the River Shannon beyond

Another view of Teampull Connor from south-west

The stone arcade at the side of Teampull Connor

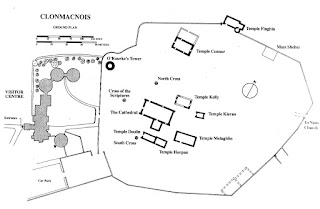

Ground plan of Clonmacnoise by Peter Harbison

===============

Lost churches

The standing remains at Clonmacnoise are not the whole story. The footings for Temple Kelly can be seen to the north of the cathedral. Old plans from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century show other churches, now long gone. These included Temple Gauny and Temple Espic along by the south boundary wall and Temple Killin to the east of Teampull Finghin and on the north boundary wall. [Tomas O Carragáin, Churches in early medieval Ireland (Yale University Press, 2010), p. 216]

Of course these lost churches were built of stone and it is unknown how many lost buildings were built of timber or wattle.

================

Conclusion

On my 2016 visit I didn't get time to visit the Nunnery complex which is about 500 meters north of the main monastic site. One should always keep back another excuse to visit Clonmacnoise!

For further reading on Clonmacnoise the two volumes of seminar papers published in book form are highly recommended.

===============

End of post

===============

No comments:

Post a Comment